PENNSYLVANIA, USA — Out of all endangered birds in Pennsylvania, the great egret may be a top contender for having one of the most interesting backgrounds.

While these birds don't call the Keystone State their native home, they arrive in flocks during breeding season - or at least, they used to.

The majority of the species is distributed along the southeast areas of the country, however, during migration the colonies drift northward into south-central Pa. to utilize their nesting habitats.

The active sites are easy to spot, with the entire colony opting to consistently remain in close quarters with each other. Both the male and female egrets work together to build their nest, made up of sticks, which are typically found nestled up high in trees.

Egrets are known to lay an average of three to four eggs during their nesting period, with incubation being an almost month-long task that both parents take part in.

The breeding residents arrive in March and would nest in a variety of areas throughout Pa., most commonly in trees or shrubs near water sources. However, as the years pass, the number of active nesting spots has shrunk statewide.

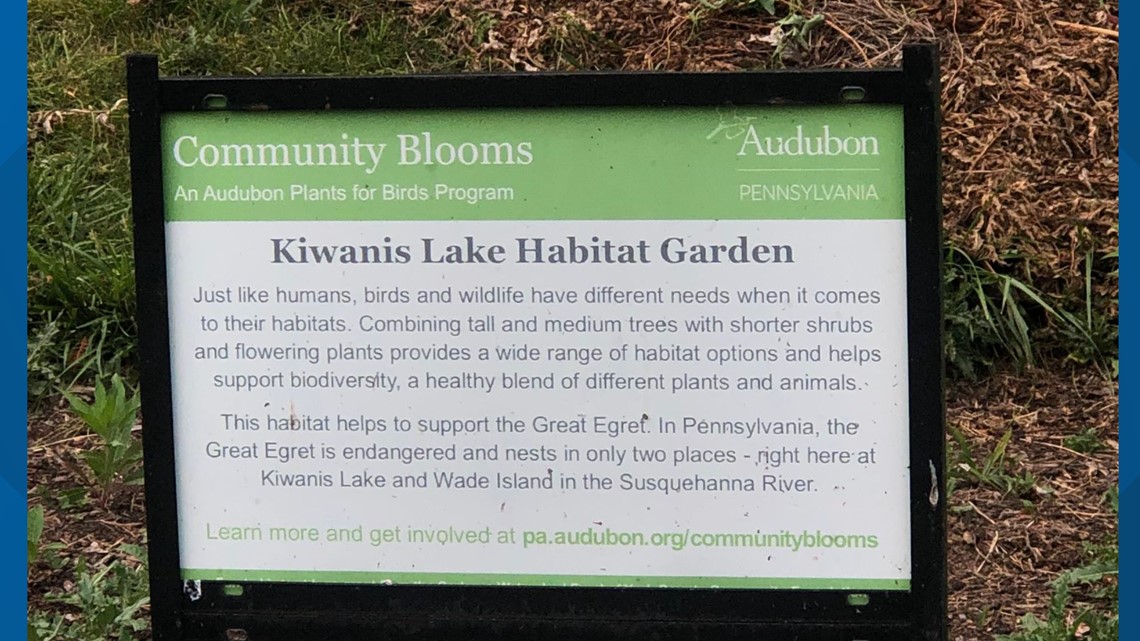

There are only two active nesting locations left in Pa.: Kiwanis Lake in York County, and Wade Island, located along the Dauphin County portion of the Susquehanna River.

Both of these nesting sites are currently listed as Pa. Audubon Important Birds Areas, but it begs the question: how did it get to this point?

HISTORIC THREATS

The great egret's breeding plumes tend to be admired by whoever is lucky enough to catch a glimpse, but unfortunately, they attracted the attention of hunters during the turn of the 20th century.

Hunters began killing the birds in significant amounts to harvest their feathers so that the distinctive plumes could ultimately be used to accessorize hats.

"Exaggerated hats were all the rage. They were a fashion statement, and these breeding plumes became an important component of those hats," recalled Pa. Game Commission's Endangered Bird Biologist Patti Barber in the organization's threatened and endangered species YouTube series. "The populations were decimated by the feather collectors, and it's part of that loss that helped the public recognize that they were losing an important part of their natural world for a fashion trend."

Right before the species was nearly wiped out, the Lacey Act of 1900 and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 were put into place. These two key pieces of legislation sought to provide protection to help rebuild, but many wondered if it was too late for change.

The National Audubon Society was founded around the same time the protective acts passed. They honored the great egret species by featuring one on the logo for their non-profit, which fights for nationwide bird conservation efforts.

As time marches forward, more great egret colonies decide against returning to the Commonwealth to breed, and while hunting isn't their biggest concern nowadays, the coast is still far from clear for the species.

Pa. residents near Lancaster and Philadelphia County respectively have both witnessed the abandonment of colony sites, with Lancaster's in 1988, and Philadelphia's in 1991.

"In terms of the difference between the two populations, the one that we monitor in the Susquehanna is an actual river island, whereas the York County population has established itself in a rather urban setting," stated Sean Murphy, a state ornithologist for the Pa. Game Commission.

CURRENT THREATS

A potentially functional nesting spot for great egrets needs to check off a few boxes before the colony decides on settling in, and each year brings more challenges when ensuring everything's up to code.

While protective measures have been put into place, the birds currently battle threats such as habitat loss, water pollution and nesting colony disturbance.

"The most urban sites are definitely at the forefront of potential disturbance from human activities, but that doesn't rule out things that can happen at [Wade Island], where it's a little harder to monitor," said Murphy.

Researchers also noted that boat traffic has the potential to disturb nesting egrets, along with washing out their shallow foraging areas.

Since nests are extremely vulnerable to public disturbance and direct harm, the Pa. Game Commission asserts that all known nesting colonies be closed to public intrusion and preserved from developmental pressures.

"Most of the [threats] are direct persecution, habitat loss and toxins introduced into the environment. They are things, even if they were unintended consequences, that we human beings did that changed the natural environment so that it was inhospitable," stated Barber. "When we take those responsibilities seriously, we change the discussion."

CONSERVATION EFFORTS

When looking at the data gathered from the nesting sites at Wade Island and Kiwanis Lake, there is a clear difference between how they both function.

"The York County population is considerably smaller. [Kiwanis] is a manmade lake, with some trees around that the egrets have taken a liking to, and they have been able to maintain a population there," said Murphy. "[The populations at Wade Island] have fluctuated up and down [over time], but they seem to be rather consistent."

When planning out conservation efforts for the Dauphin County colony, officials with the Pa. Game Commission, led by Patti Barber, spend a maximum amount of two hours a year gathering data on Wade Island, all while being in a straight line to minimize disturbances.

However, at Kiwanis Lake, individuals can see the great egrets nesting at a much closer and personal level. The chosen, albeit unusual, location of the birds has placed the colony directly in a public park, where many York residents spend time fishing or enjoying the weather. The only thing separating the endangered egrets from the public is the height of the trees and various informative signs scattered in front of the nesting site.

"The human activity [at Kiwanis Lake] might offer some advantage. There may be less predators around because the site is so disturbed. They are provided the protection to persist there, and they seem to be doing well," stated Murphy. "It gives Pennsylvanians a really interesting opportunity to sit and observe the large charismatic birds' nesting behaviors."

Since 1990, the great egrets have been on Pa.'s threatened and endangered list, and many officials believe that this addition helped better place the birds in the public eye and support the passing of future protective legislation.

"In terms of species protection, that list is one of our best tools in the toolbox to protect the species and make sure they are around for future Pennsylvanians," said Murphy. "Those laws allow us to protect those birds during the nesting season, and a lot of partnerships make sure those areas and habitats are protected outside the nesting season. Currently, the law allows us to protect while the breeding birds are present, but not necessarily after."

According to Murphy, great egrets being state-listed birds further helps to minimize habitat disturbances, as environmental review processes are necessary for any potential development project that comes to light.

WAYS TO HELP

Fortunately, if one wants to participate in helping the conservation of great egrets, it's not hard.

"There's a lot of things people can do to help: Limiting the use of lawn fertilizers and chemicals, [since they] wash into the waterways and cause problems downstream [helps], cleaning up fishing lines, [because] I can't tell you the number of times I've seen birds tangled in fishing line," stated Barber. "They can drown from it, they can get wrapped around it in a way that they cant forage, so they starve to death."

Barber additionally stresses the importance of using lead-free tackle and how it directly aids in higher water quality, which in turn leads to higher-quality food resources for the colonies.

A harder part of conservation that a lot of nature lovers may struggle with is that leaving the nesting birds alone helps them have a much greater shot at survival.

"You definitely want to give them space. If there's a bird in a nest, and you're close enough that the birds leave, it probably means you're a little too close," said Murphy. "It's important to back up and give them the space that they deserve for several weeks."

When observing the great egrets, it's hard to imagine a bird like that calling Pa. home. The time to protect these large feathered friends is now so that we can ensure future generations will have a chance to see them take flight through the Commonwealth.