Sperm Whales

Physeter macrocephalus

Historical Significance

Though not as talked about as the California gray whale, humpback, or blue, the sperm whale is an animal of extremes. These whales are unique for having the largest brain of any animal, being the largest toothed predator, the most sexually dimorphic cetacean species, and their highly social way of life. However, it was their industrial value that initially grabbed the attention of humans. Through the 18th and 19th Centuries, sperm whale oil was responsible for keeping the streets lit at night, was the main ingredient in clean-burning spermaceti candles and lamps in homes and businesses, and was the main ingredient in soaps and cosmetics. Lastly, spermaceti oil lubricated the machines of the Industrial Revolution. Sperm whales were like oil reservoirs, while the whalers were the Shell or BP of the era. Because the sheer volume of spermaceti oil contained in one animal was so high, sperm whaling (the hunting and processing of sperm whales) became one of the most profitable endeavors of the time.

Sperm Whale Facts

Order: Cetacea

Suborder: Odontocetes (toothed)

Family: Physeteridae

Species: P. macrocephalus

Status: Vulnerable

Weight: 15-45 Tonnes

Sperm whales were not only coveted and hunted for their monetary value, but they were also feared and pondered by scientists and literary scholars since the first whale was hunted in 1712, off the coast of Nantucket. Herman Melville, who was also a whaler, used the sperm whale as his muse in one of the world’s most recognized novels, Moby Dick. Melville describes “…touching the great inherent dignity of the sublimity of the sperm whale…”. Or there is the lesser-known Natural History of the Sperm Whale written in 1839 by an English surgeon and on-deck whaling observer, Thomas Beale. Beale’s novel is known to be a work selected by scholars for holding cultural importance while contributing to our base knowledge of sperm whales today. While there are many more books, Beal’s novel is just another example of the impact these magnificent animals have had on our history and culture. Sperm whales have been and continue to be the muse and subject of study for many writers of folklore, scientific journaling, research, and literature.

Size and Identification

The most notable physical feature of the Sperm whale is its robust, square-shaped head, which takes up about 1/3 of its body length. The sides of the body have a bumpy or wrinkled appearance starting behind the head. The signature of sperm whales is a relatively small, narrow bottom jaw lined with the largest teeth of any predator in the world. Though the upper jaw is devoid of teeth, it is lined with sockets perfectly formed to fit the lower teeth. The upper jaw is merely a structure encompassed by the spermaceti organ. The box-shaped head is likely scarred from feisty past prey, natural ocean hazards, or other sperm whales. A single blowhole is set to the front, left side of the head. Sperm whale pectoral fins are relatively small and paddle-shaped. The tail fin or flukes are one of the only features of the sperm whale that is not particularly unique, with a general triangular appearance. From the surface of the water, the sperm whale may resemble a giant, outstretched log with a short, rigid dorsal fin near the middle of its back. Males can reach lengths of up to 55 feet (17 meters) and up to forty-five metric tons. Females on the other hand are much smaller, reaching 36 feet (11 meters) in length and roughly fifteen metric tons. The female sperm whale’s head is less prominent, yet still taking up one-quarter of her body mass.

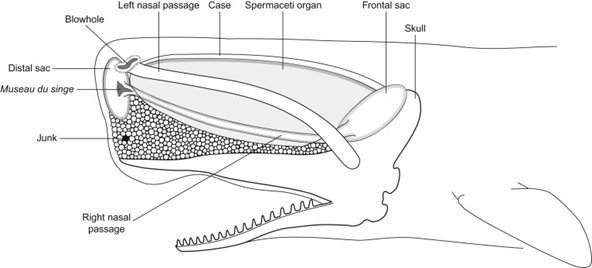

Spermaceti Organ

Among the many features that set sperm whales apart from other cetaceans is the distinct spermaceti organ – or as the whalers dubbed it, the “Case” (Fig 1). This unusual adaptation is so significant that the skull has evolved to be a supportive basin for the massive organ to rest in. Taking up to 33% of the animal’s mass, the spermaceti organ embodies the head and is encased in a muscular sheath containing soft tissues comparable to a sponge saturated in oil – spermaceti oil. The skull is separated from the spermaceti organ by an air-filled cushion, supplied by the animal’s right nasal passage. The nasal passage separates into two, one running above the spermaceti organ to the blowhole, and the other below, following between the organ and another huge structure whalers referred to as the “Junk.”

Fig 1

Since the 1700s, scientists have sought to understand the purpose of the spermaceti organ and the overall anatomy of sperm whales, and many did this by observing the flensing of the whales on board whaling ships. A great deal of the known biology of sperm whales came from scientists’ observations and meticulous notetaking aboard these floating processing plants, by examining the carcasses of butchered whales, resulting in an in-depth body of knowledge on the biology and anatomy of sperm whales. Nonetheless, even modern-day science cannot be fully certain of the complex spermaceti organ’s function, albeit the current scientific consensus strongly supports that the organ is a specialized adaptation designed for diving, deep-sea navigation, hunting, communication, and potentially sexual selection.

Range

Sperm whales occur in all the world’s oceans, through all zones and hemispheres. They can be found within and around the deep trenches and ocean canyons offshore, following their prey items - primarily squid (though their choice of prey varies geographically). They can be seen in California waters year-round and are in highest concentrations from April through mid-June, and from late August through mid-November. They can be seen from our shores in all seasons other than winter. Otherwise, females together with the young and juvenile family members live largely in tropical or subtropical waters, as the males journey closer to the Arctic and Antarctic poles in search of giant squid; squid that are in some cases larger in length than the whales themselves. The largest males can be found near the polar pack ice regions, although, most will return to the tropical zones to breed a few months out of the year.

Echolocation and Diving

Imagine being born into a featureless, three-dimensional, dark, and liquid world, where your only way to navigate the mysteries of your surroundings is to make sounds with your head in order to “see.” Because in water sound travels at a rate five times faster than in air, making sound the primary sensory cue for the majority of marine mammals. And if you were a sperm whale, you would have the use of the most efficient biosonar tool that nature has ever created – the aforementioned spermaceti organ. It is theorized that this adaptation produces powerful echolocation clicks, creating pulses that begin by passing air through what is called the museau dusinge, or the “monkey lips” before it passes through the spermaceti organ (refer to Fig 1) - here the pulse bounces off the air-filled cushion where it is reflected back through the junk and into the ocean through multiple layers of acoustic lenses within the junk. And just like man-made ultrasound, the pulses reflect off any objects or entities in the sperm whale’s surroundings, returning an “image” for the animal to identify. Studies show that these powerful clicks are directionalized, can travel great distances (2,600 feet per half second) as it locates, and if close enough, acoustically debilitates prey.

The ability to “see” in pitch blackness goes hand-in-hand with the ability to dive to the deepest, darkest, and most remote places on the planet. Having this efficient built-in biosonar and the physical ability to routinely reach depths of 2,000 feet (610 meters) and return to the surface every forty-five minutes, gives sperm whales the advantage to seek out the larger prey items that lurk at the depths. However, the largest and most mature adults can reach depths of 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) while holding their breath for up to two hours. Being able to withstand the crippling pressures by collapsing their ribcage and slowing their heart rate to just a few beats per minute(bradycardia), all while supplying only the vital organs with oxygenated blood. As a result, sperm whales can descend comfortably to depths that human free divers can only dream of.

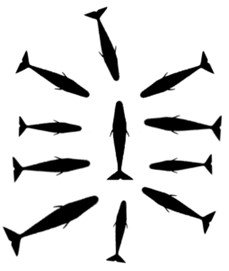

Fig 2

Social Lives

“Maybe we’re looking at sperm whale behaviors as a way to explore ourselves” – Jeff Jacobsen, 2023.

When commercial whaling began and long into the 19th century, sperm whales were largely declared as dangerous and hostile animals. For example, in 1839, French zoologist Baron Curvier agreed with Herman Melville when he wrote: “There is no animal in creation more monstrously ferocious than the sperm whale”. In spite of this popular opinion, there were those who debated the claim such as Thomas Beale, who saw the sperm whale as “a most timid and inoffensive animal… readily endeavoring to escape from the slightest thing which bears an unusual appearance”. Fast-forward nearly 200 years, and current literature has shifted to regarding whales as “gentle giants,” including sperm whales. Modern studies have revealed that not only have sperm whales shown to be docile and hard to study due to their retreat to the depths, but that they are more like us than we could have thought.

Furthermore, much like humans, sperm whales are highly social animals. Especially so are the females and young adults who travel together in groups of up to 35 individuals, usually accompanied by one to three adult males. As some individuals come and go from the group, evidence has shown that some of the females travel together for years.

Similarly, sperm whales exhibit behaviors of empathy and care for others. One of the first reports of the “rosette” or “marguerite” formation came from Hal Whitehead and Jonathan Gordon as they led a research team through the Indian Ocean to follow and study sperm whales between 1981 and 1984. Whitehead recalls, “They were twisting and maneuvering into unusual patterns, including a star…Their heads were together at the center, but their bodies radiated out in different directions” (Fig 2). This flower position has been seen many times by observers and scientists in the following years and has been established as a defensive position against a threat, especially in protecting one of their young or weak, who they position in the center. One such example is when a group of killer whales (Orcinus orca) began to attack a group of nine sperm whales in a 1999 account. When a sperm whale was pulled from its position in the rosette, two or more individuals would leave the safety of the rosette to assist their isolated companion. Putting themselves directly in harm’s way to try and preserve the life of the other.

Likewise, the way sperm whales care for their young is reflective of how many human parents and relatives take care of their own. For example, the birth of an infant is a rare and social event. With a gestation period of 14-16 months, sexually mature female sperm whales will only give birth once every 4 – 7 years. And according to the researchers Weilgart and Whitehead’s rare eye-witness account, the group of sperm whales in the mother’s company will gather around her as she goes through labor. Once the calf is free from the mother’s womb, it gets “passed around” to the other adult females while it awkwardly learns to swim, all while getting jostled and nudged. The reason for this is not clear, but after some time the calf is left alone with its mother to suckle and bond while the other whales keep the protective barrier around the pair.