- India

- International

De-extincting the dodo: Why scientists are planning to bring back the bird to Mauritius

Geneticists and conservationists have joined forces to re-introduce the Dodo, extinct since the late 17th century, to its once native habitat in the island of Mauritius. How is this being planned, and perhaps even more interestingly, why?

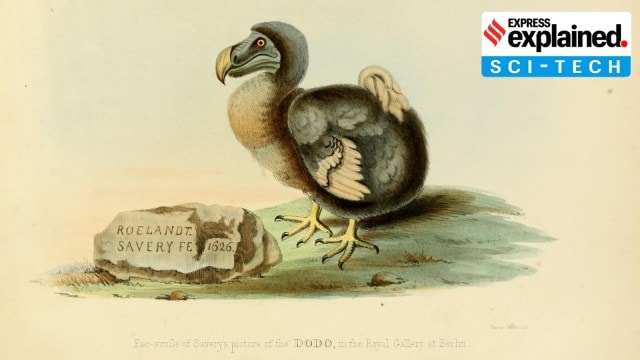

This is a facsimile of a 1626 painting of a dodo by Dutch artist Roelant Savery. Without photographs of the bird, such visual representations have been crucial to the myth-making behind the dodo. (Wikimedia Commons)

This is a facsimile of a 1626 painting of a dodo by Dutch artist Roelant Savery. Without photographs of the bird, such visual representations have been crucial to the myth-making behind the dodo. (Wikimedia Commons)The simile ‘(as) dead as a dodo’ is used, often figuratively, to “stress that someone or something is dead”. Since the last of its species died, sometime in the final two decades of the 17th century, the tubby flightless bird has become somewhat of an ‘icon of extinction’.

An ambitious new project — a collaboration between genetic engineering company Colossal Biosciences and the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation — promises to not just bring the dodo back to life, but also re-introduce it in its once-native habitat in Mauritius.

How did dodos go extinct? How will they be resurrected? And why? We explain.

Why dodos went extinct

Popular representations make it appear that the dodo “deserved” its tragic fate. “What other fate could there have been for such a foolish-looking ground pigeon?… Raphus cucullatus had the air of a bird that stood still with a blank stare as the scythe of extinction lopped off its head,” Riley Black wrote (satirically) in National Geographic in 2011.

A reconstructed dodo skeleton on show in Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, Germany. (Wikimedia Commons)

A reconstructed dodo skeleton on show in Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, Germany. (Wikimedia Commons)

This sentiment, however, paints a one-sided picture. Dodos were not simply dumb. They were remarkably well-adapted for the ecosystem they inhabited, with its abundant supply of food, and lack of major predators. Their extinction, thus, was far from inevitable — that is until humans arrived on the scene.

Dutch colonists first landed in Mauritius in 1598. Dodos disappeared around 80 years later. Not only did the Dutch hunt the meaty bird, but the animals they brought with them — dogs, cats, rats, etc.— wreaked havoc on the defenceless dodos and their eggs.

It is the human hand in the dodos’ extinction that has made for its enduring cultural resonance. As environmental historian Anna Guasco wrote in ‘As dead as a dodo’ (2020): “It is the canary in the coalmine of anthropogenic destruction. Its extinction is seen as the inevitable outcome of human interaction with nature.”

How geneticists plan to bring the Dodo back

To de-extinct a species, the first thing required is accurate and complete genetic information. This is known as a species’ genome — each genome contains all of the information needed to build that organism and allow it to grow and develop.

Beth Shapiro, Colossal’s lead paleo-geneticist, has successfully sequenced the entire genome of the dodo using DNA extracted from a skull in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Denmark. This is now being compared to the genome of the Rodrigues solitaire, the dodo’s closest (also extinct) relative to identify just what makes a dodo, a dodo.

Colossal has also sequenced the genome of the Nicobar pigeon, the dodo’s closest extant relative, and found its primordial germ cells (PGCs). PGCs are basically embryonic precursors of a species’ sperm and egg.

The extant Nicobar pigeon, endemic to India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands. (Wikimedia Commons)

The extant Nicobar pigeon, endemic to India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands. (Wikimedia Commons)

This is where the ‘magic’ begins. The Nicobar pigeon’s PGCs will now be edited to express the physical traits of a dodo, with the help of the insight gathered from the comparison of the genomes of all three birds. These edited PGCs will then be inserted into the embryos of a sterile chicken and rooster, who will act as ‘interspecies surrogates’. In theory, when the chicken and rooster reproduce, they will give birth to a dodo offspring.

“Physically, the restored dodo will be indiscernible from what we know of the dodo’s appearance,” Matt James, Colossal’s chief animal officer, explained.

The challenge

“Colossal’s idea is a sound one… [but] because of the complexity of recreating a species from DNA …[it] can only result in a dodo-esque creature,” Julian Hume, an avian palaeontologist at London’s Natural History Museum, told CNN.

“It will then take years of selective breeding to enhance a small pigeon into a large flightless bird. Remember, nature took millions of years for this to happen with the dodo,” he added.

Beyond complications posed by genetic engineering are the challenges that lie ahead. While de-extinction is currently in vogue, a proposal to reintroduce a long-extinct creature to its once-native habitat is nearly unheard of.

Mauritius of the past simply does not exist anymore, “much of it has already been replaced by sugar cane, buildings, villages (and) reservoirs,” Vikash Tatayah, founder of the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, told the media. For dodos to survive, invasive species including rats, feral cats, pigs and dogs, monkeys, mongooses, and crows may need to be “excluded, rehomed or even controlled,” Tatayah explained.

This is why the foundation is considering reintroducing dodos not to the main island but to nearby Round Island and the islet of Aigrettes, both of which are uninhabited and relatively pristine.

So, why go through all this effort?

Tatayah believes that reintroducing the dodo to Mauritius can help restore its fragile ecosystem, citing “mutualistic relationships which have broken down since the loss of the dodo.” The bird’s large beak indicates that it consumed large-seeded fruits, and thus played a role in the seeds’ dispersal, he said.

Moreover, the technology that Colossal would use to revive the dodo would also help to conserve and restore other avian populations “at the brink”.

But perhaps most significantly, this is a project driven by symbolism. Ben Lamm, CEO and co-founder of Colossal, argues that “restoring the dodo gives us the opportunity to create ‘conservation optimism,’ that hopefully inspires people around the globe, in a time when climate change, biodiversity loss and politics can make things seem hopeless.”

Looking at things this way, there is perhaps no better animal to de-extinct than the one most associated with human-caused extinction.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

May 03: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05