Critics Page

“PUTTING YOURSELF IN A PLACE WHERE GRACE CAN FLOW TO YOU”

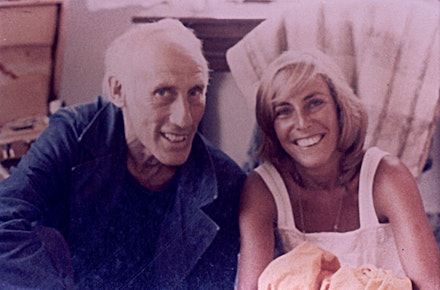

Nancy Goldring on Robert Lax

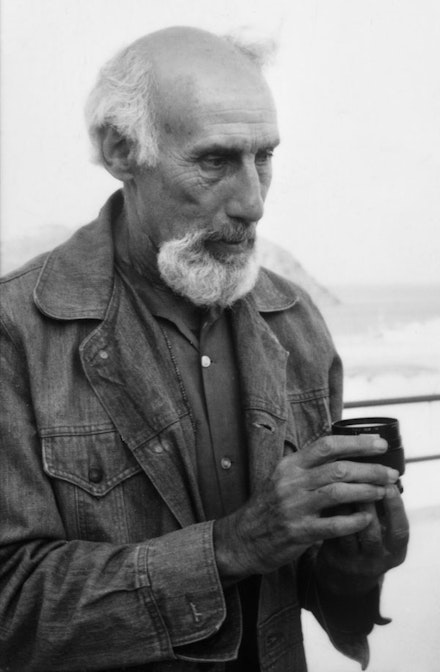

“One of the great original voices of our times … a pilgrim in search of beautiful innocence, writing lovingly, finding it simply, in his own way,” Jack Kerouac said of American poet Robert Lax (1915 – 2000). Lax lived on the Greek island of Patmos much of his life, writing small crystalline poems that recall the formal severity and emotional richness of his friends Thomas Merton and Ad Reinhardt. In 1978 artist Nancy Goldring met Lax and began a friendship which continued to his death. During that time, Goldring developed her unique work process called “foto-projections” that involves layering slide-projected images onto drawings which are re-photographed in cycles, becoming tangled webs of time, space, and memory. Here she recalls their time together and collaborating on the installation Legend (1991).

Nancy Goldring: I arrived on Patmos in May 1978 age 33. My original plan was to stay on nearby Samos until I realized living alone on an island with an army base might not be a good idea. Advised by a Dutch family that Patmos was a good place to be “lonely,” I set off on a tiny boat filled with priests and goats. The last to exit the boat, having been elbowed out of the way by the holy men and their flock, I managed to negotiate a simple room with exquisite views looking up to the monastery and out onto the harbor. It was low season with few tourists and the locals friendly. Soon people began to ask if I had met the poet, “Have you met Petrus? He comes to town for his mail, you’ll recognize him.” Maybe two weeks passed before he arrived in town. He came looking for “the artist”—and so we found each other. I wrote about our encounter in my journal. I’ll read it:

Roberto Petrus Lax. Has been here for 16 years. He walks around the island, bushy white hair, wild blue eyes, stubble beard, with an abstracted gait. His loose blue jeans identified him as an American and his special lean look revealed him as not a Greek. Our first conversation I felt as if I could babble on and on and he wouldn’t halt the flow. We had stories to tell each other, travels, places. “America is just a place for us,” he laughs, tells stories, speaks to everyone in town with a friendliness all his own, has been so removed from the world that I grew up in, and yet it seemed not foreign to his experience. He hasn’t lost himself and makes immediate contact for someone who would be so lonely.

Many called him “the hermit”—but that wasn’t remotely true. There was always a steady stream of visitors. All the surfaces of his little house were covered with piles of letters. His was a rich and complicated life. Imagine, Avedon flew in on a helicopter to photograph him.

He looked carefully and long at my drawings and seemed to understand them. He didn’t need make any complimentary comments. He felt they suited their poems.

That was the summer I took only one book, Wallace Steven’s Palm at the End of the Mind. I didn’t want to get lost in novels, I wanted to be there—

That they suited their poems seemed important to me too. We stopped in the restaurant with a view I had used in one of the drawings and the owner asked if I were his daughter. She insisted that we absolutely resembled each other. He confirmed her beliefs and we laughed on it. He recited at a fast clip, stopped only to check his watch, and asked if I had seen the monastery and told me the cross was from the sixteenth century and then he ran down the steps as if chased by the devil.

That is the entry about my first meeting with Lax . I didn’t know what I was “finding” but our conversations were spontaneous and intense. He wanted to know what I thought of this or that artist. People like Joel Shapiro, Reinhardt, Newman, Piero della Francesca. And then we started to see each other everyday. I can remember, he’d come at sunset and bring whatever he had written. During my second visit—it might have been ’82 or ’83—I would draw in the afternoon and he would sometimes yell from his house high on the hill above mine to see if I was ready before descending. One time he just came down. I was just finishing a drawing and I called out “I’ll be out in just a minute.” He sat down out on the terrace. Without knowing it over an hour had passed before I finished the drawing. I thought, “oh my god Bob is here, what I have done? How rude!” and I rushed out to find him just sitting calmly. “Oh, I was just counting the birds.” Then he read his poems and it was all fine. “You have a wonderful sense of order,” he said—which I thought it was a generous thing to say about someone who had just kept you waiting for an hour.

This was the last entry written the day I left that first summer in 1978:

More and more I discovered in him and his life the peculiar blend of mundanity and purity—

And that is really what it was. He was so savvy and yet so profoundly pure, an impossible combination.

That evening he was discouraged. Always encouraging to me but that evening I felt as if I wasn’t able to say the right thing to assuage whatever it was that worried him. It was too hard to think of not seeing him again soon.

For two months we saw each other everyday and I guess we were both very sad about my leaving.

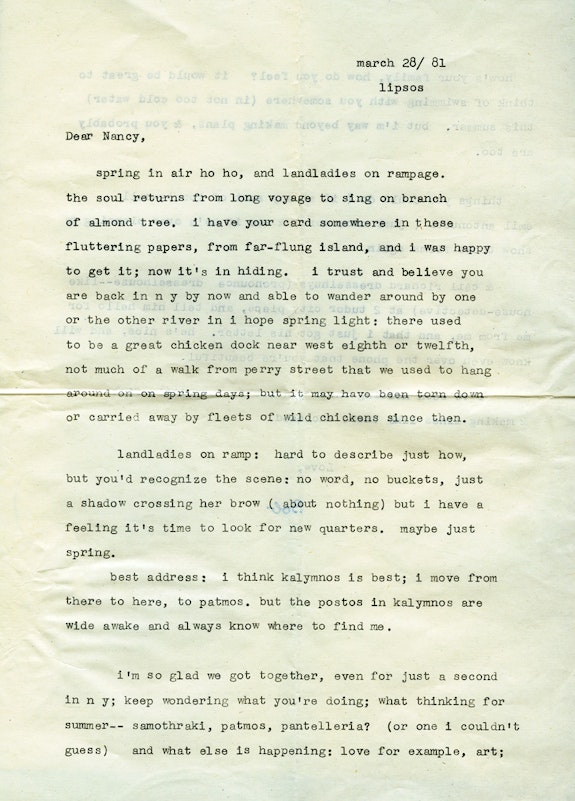

Jarrett Earnest (Rail): Between the first trip and the next were you in touch by letter?

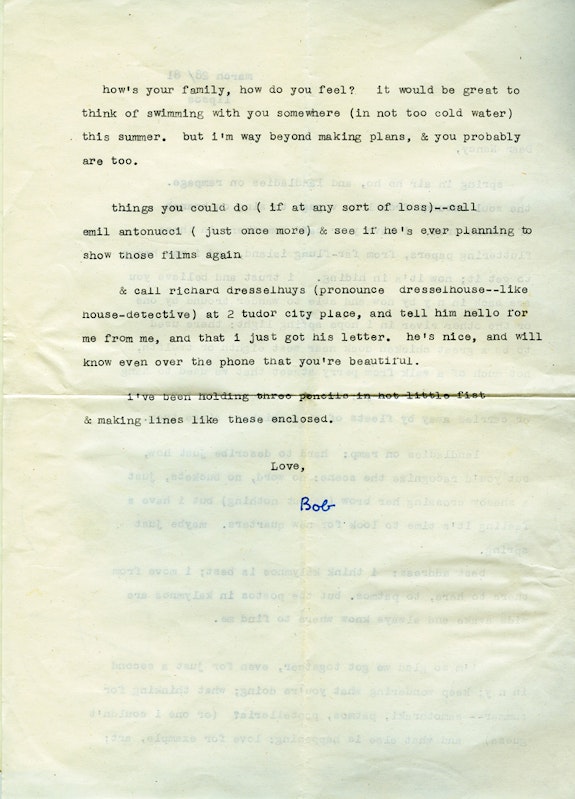

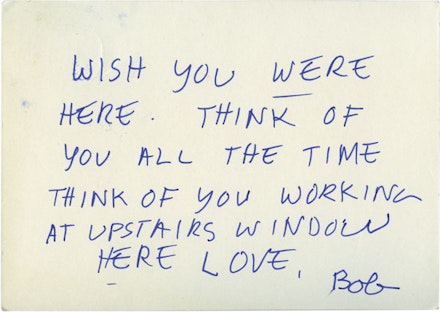

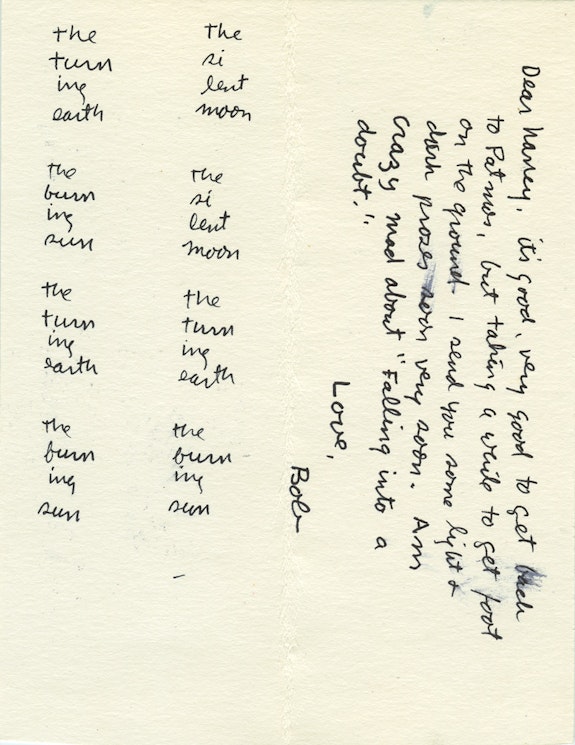

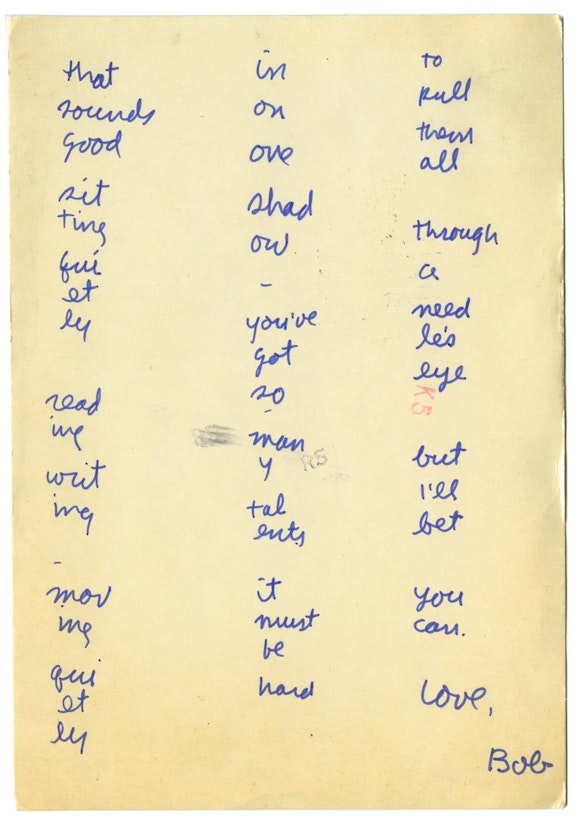

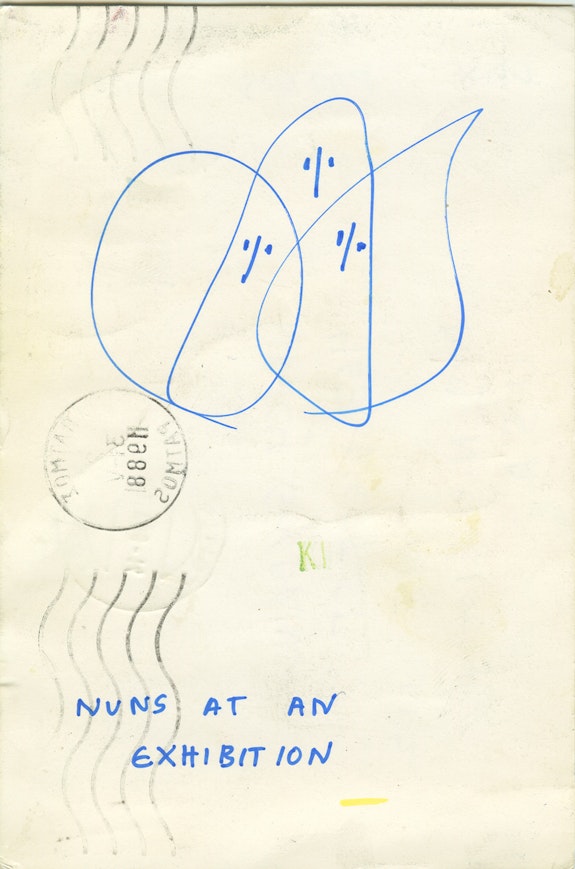

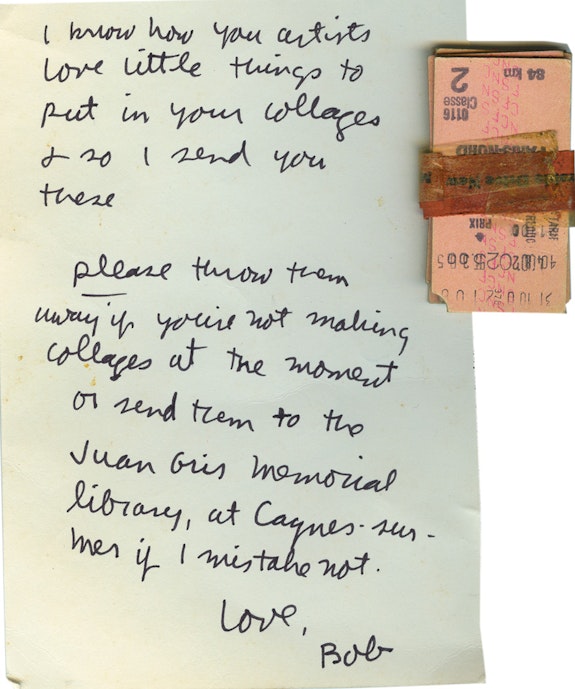

Nancy Goldring: Yes, letters all the time—it never occurred to use the phone. They were always about work or “oodles and oodles of love” or funny things. Once he sent a packet of metro cards from Paris that had been used and said “I know how you artists love little things to put in you collages, so I send you these. Please throw them away if you’re not making collages at the moment. Or send them to Juan Gris.” He would sometimes sign them with silly names which is what he and Thomas Merton did in their correspondence a lot. Or a short poem like this:

On

the

walls

of

my

co

coon

spring rain

Rail: Why was he on Patmos?

Goldring: This is what he told me following a long conversation about his religious beliefs: When he was young he spent a lot of time with a rabbi whom he admired asking questions and questions. He was born Jewish, and after all his questioning it didn’t make sense to him. And of course he had a close friendship with Thomas Merton—they were baptized in the same church on 125th Street. Lax was writing movie reviews for the New Yorker, and he said one day he couldn’t pick his head up off his desk and really had to get out of town. The next thing he knew he was standing in front of a luggage store and before he could blink he was traveling with the circus. Then after that, he says—this is the way he articulated it—he saw a postcard of a medieval painting in which there was “a big man on a little rock”—St. John of Patmos. He said, “I think I’d like to be like that.” Patmos is one of the most sacred Greek islands with this beautiful monastery which you could visit back then. He knew every little chapel and would go and perhaps pray in his own way. They called him Petrus for Saint Peter, the rock. I don’t think he went to church to pray, but he did visit these little sacred chapels and he would never eat without saying a blessing. Once he wrote “putting yourself in the place where grace can flow to you” and I think that answers why he was on Patmos. His profound minimal sensibility that he shared with Reinhardt really comes from that spiritual core. These poems are like icons. He always used to tell young writers who made pilgrimages to him: “If you can say it in two syllables, don’t say it in three; if you can say it in four words, don’t say it in five—two is even better.” He would absolutely get things down to their most essential.

Rail: One poem I love that was broken into:

sea

sun

sea

sun

sea

sun

everything in its season.

Goldring: You know how he made those poems? We used to go swimming in a leaky old boat with his friend Michalis who would row us to a tiny cove near the harbor. He would recite these poems through his snorkel—“sea … sun … sea … sun … sea … sun …” while he was breathing in and out, paddling around, to the fish.

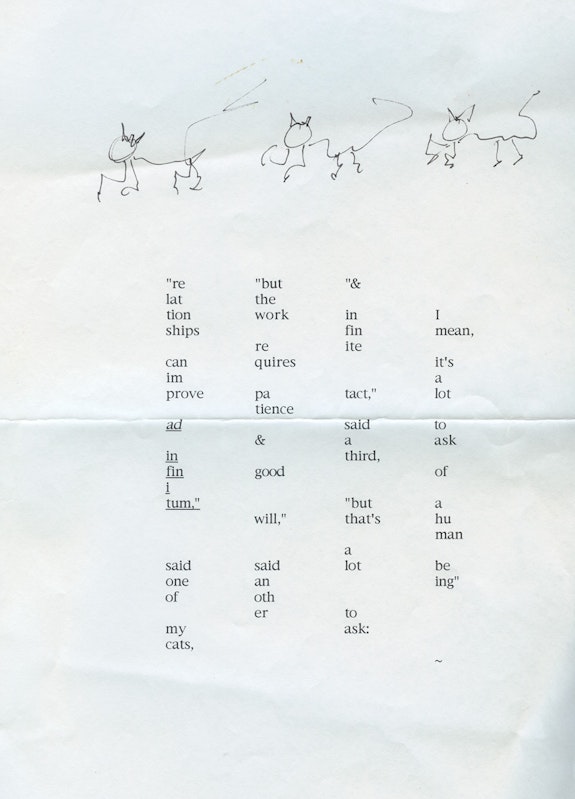

Rail: In conversations about your drawings, and his poems, what was the nature of your interest in each other’s work?

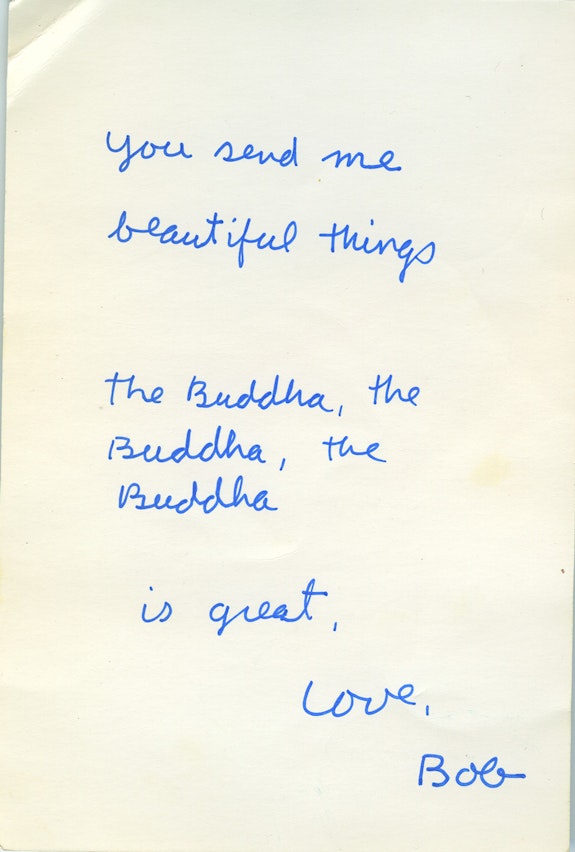

Goldring: It was not so much talking about them but a response within his poetry to them. We seemed to be finding more and more affinities within our work or how we worked. I sent him an image I made after visiting Borobudur and he wrote back:

You send me beautiful things.

Buddha, the

Buddha, the

Bud

dha

It would be interesting or useful to trace the ways he affected my work—it was always something I felt. The thing about drawing in Greece is that the light is so clear. So clear that it makes you think you can really see everything, so if you draw and you really want to see the quality of every mark, there is no place like Greece. I think that was conducive to the pairing down of things. 1978 was the year I can mark where I started drawing. Of course I had been drawing for many years and had already shown my drawings and foto-projections but this is when it felt like I really can draw or know why I am drawing, that it was something profoundly connected to me. I think Bob had a big part in this.

The last visit to Patmos was to work on our installation project. I had been wanting to do a piece that was a “legend,” having just revisited Arezzo to see The Legend of the True Cross because it had been so important to me when I was a student in Italy. Piero’s epic narrative is so crystalline while the narrative brings to life important mythical/historical moments. I wanted to make my own legend with Lax—one that was situated in our contemporary world. In the background was the skyline of Manhattan with the World Trade Center towers—in ’88 or ’89 I had done a commissioned piece for the opening of Ellis Island using the New York skyline. That view became the architecture or structure of the installation. The foreground was entirely built with collages from the newspaper—a kind of ruined structure within which you could detect posed dancing figures. In the installation as the slides change you see suddenly that something happens, the world goes dark and then overwhelmingly light, a man parachutes out. Then the city goes up in flames. Firemen come and put the flame out, at the center a beast—actually an iguana from the Galapagos—goes up, appears briefly within the fire, and finally a glowing rock remains. Then the cycle begins again. We sat in his house each afternoon, looking at the images and Bob would speak the text. We planned that each image would dissolve to white and Lax’s text would appear on the screen—a beautiful clean yellow. Then we went up to one of the chapels and I recorded him reading it. There were several versions.

I first showed our project in 1991, long before 9/11. The morning of 9/11 the people who had bought the series called me on the phone because they couldn’t believe it, it was as if the imagery in Legend prefigured what we were living through. Some years ago I was asked to rebuild the installation for a 9/11 remembrance—at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum in Connecticut. They requested that I speak, but I found a poet who had been a friend of Bob’s who lived in the area and had him come read some of Bob’s funny poems. I loved that at Lax’s memorial his friends read mostly funny poems, which was great because he was rarely melancholy, maybe serious sometimes. I am sure I laughed more with Bob than any person I have known. He was incredibly funny.

Robert Lax “Legend”

There are no facts

Only events

THE BEGINNING

OF THE JOURNEY MOVE

THE END

STOP

THE BEGINNING

OF THE JOURNEY MOVE

LIGHT IS

LIGHT IS NOT

LIGHT IS

AND IS NOT

THIS THAT

IS IS

LAND LAND

HERE THERE

THE THE THERE

FAR FAR HERE

THE THE THERE

NEAR NEAR THERE

ASPECT

OF

CITY

ASPECT

OF

SKY

SUN SUN

ON ON

HORIZON WAVE

RE RE

FLECTS FLECTS

ON ON

WAVE HORIZON

TANGIBLE

VISIBLE

INTANGIBLE

INVISIBLE

LESS THAN

TANGIBLE

LESS THAN

VISIBLE

BARELY

THERE

AND

NOT

THERE

THIS THAT

MO MO

MENT MENT

THIS THAT

PLACE PLACE

MARBLE

FLAME

GRANITE

FLAME

THE ROCK

THE ROCK

THE ROCK

WATCHING

NOT WATCHING

THIS

MO

MENT

THAT

FIRE

BURNING

FIRE

BLAZE

WITHIN

BLAZE

STILL

THE

ROCK

STILL

THE

ROCK

MOVE

STOP

MOVE

There are no facts

Only events

Contributors

Nancy GoldringNANCY GOLDRING is an artist living in New York. A founding member of SITE, Inc. an experimental architectural group in the seventies; she has received two Fulbright grants, one to Italy and another to Southeast Asia. A professor at Montclair State University, her most recent exhibitions include Galleria Martini Ronchetti in Genoa and the Architectural Association of Rome.

Robert LaxROBERT LAX (1951 - 2000) was an American poet who lived the majority of his life on the island of Patmos, Greece. The handsome volume Poems (1962 - 1997) was recently published by Wave Books, and Pure Act: the uncommon life of Robert Lax by Michael McGregor will appear September 2015 by Fordham University Press.