The term "dead as a dodo" may no longer ring true, thanks to Colossal Biosciences, which announced on January 31 that it is planning to "de-extinct" the dodo.

It's the third extinct species that the U.S. company has announced that it is bringing back from the dead, the others being the woolly mammoth and the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the thylacine.

However, many scientists don't think that bringing back species like the dodo is a good move.

"Bringing dodos back does not help the species (I'm not sure that idea makes any sense). Nor does it help the actual dodos who were victims of human activities," Josh Milburn, a moral and political philosophy lecturer at Loughborough University, told Newsweek. "It just creates new dodos. Does it help us? Creating animals just for our own curiosity does not sound respectful; it sounds like we're instrumentalising these animals.

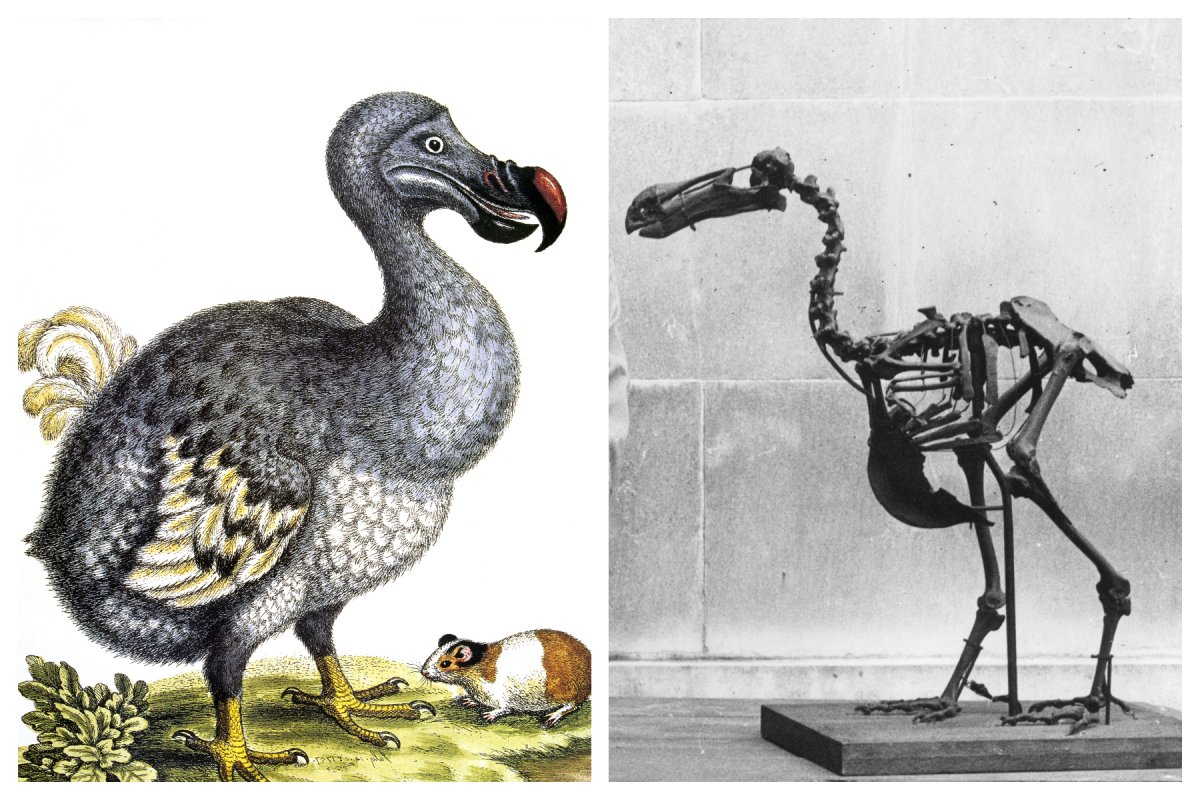

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a flightless bird native to the island of Mauritius, measuring around 3 feet and 3 inches tall. It had very few predators, so was fearless when humans arrived on the island in the 1500s. Unfortunately, it was killed en masse by sailors for food, and populations were additionally decimated by invasive species brought over by the European ships, including dogs, pigs, cats, and rats.

The dodo is thought to have gone extinct some time between 1688–1715, with sightings having dropped massively even by the 1660s. The bird had only been described for the first time in 1598 by Dutch travelers during the second Dutch expedition to Indonesia, a mere century before.

The dodo de-extinction project is only now possible due to the dodo genome having been sequenced for the first time by a team at the University of California in 2022.

Colossal plans to integrate the dodo genome into the genome of the Nicobar pigeon. These genetically altered genomes will then be grown as germ cells, which will be transferred to a surrogate chicken host.

Thanks to our incredible #SeriesB funders, we're thrilled to announce the launch of our new Avian Genomics Group, whose first undertaking will be the de-extinction of the iconic #dodo 🦤 bird. #itiscolossal

— Colossal Biosciences (@itiscolossal) January 31, 2023

Rediscover the dodo: https://t.co/qPbCBo6aLU pic.twitter.com/YLqpsJaCPC

Milburn argues that the newly de-extinct dodos would not have a good life, and neither would any of the other animals impacted by the project.

"If de-extinction efforts are successful, what will happen to the dodos created? Will they be kept in zoos for our amusement? That sounds wrong. We should not create animals just so we can exploit them," Milburn said.

"These may not be the only living animals harmed by de-extinction efforts. For example, the technology will almost certainly require the use of so-called 'surrogates' for these animals. Will these surrogates be treated with respect, or will they be confined, suffer, and face early death? These are the kinds of questions that must be asked. If de-extinction technologies involve harming living animals, then this is a strong argument against their use."

Colossal says that if it successfully brings back the dodo, they will be released to live in their ancestral home, the island of Mauritius.

"If the plan is to re-release dodos onto Mauritius, we need to ask about the impact that such a release will have on the people and animals who live there now. If the impact will be negative, that gives us a very good reason to pause," Milburn said.

There is also concern that the dodos would simply go extinct again, as the world we have created is not compatible with them.

"We don't know how long individuals of resurrected species will live but it does seem likely they may face many significant challenges, not the least of which is the potential loss of natural behaviors (hunting, evading predators, social...) that promote survival," Euan Ritchie, a professor in wildlife ecology and conservation, at Deakin University in Australia, told Newsweek.

Other scientists agree, saying that the funding going into the dodo project and the others to bring back the mammoth and the thylacine would be better spent keeping the biodiversity we already have on Earth from going extinct.

Some $150 million has been allocated to the dodo de-extinction project so far.

"I think that the general consensus in conservation circles is that the effort (time, expertise, money) would be better spent on trying to conserve and restore existing species and ecosystems," Jason Gilchrist, an ecologist at Edinburgh Napier University in the U.K., told Newsweek. "Resurrection requires huge amounts of money and investment in expertise and technology, with a relatively low probability of success."

"I feel that we should be concentrating on saving what biodiversity we still have (which we are not doing a great job of) rather than investing in projects to bring back species that we have already failed."

3. If anyone wants to donate $150 million to clone a dodo to restore Mauritius' ecosystem (that's the fundraising target), tell them to miss out the bit about cloning #dodos (because it won't happen), & spend it on actual ecosystem restoration, like controlling invasive species. pic.twitter.com/0fYqabuC1G

— Jack Ashby (@JackDAshby) January 31, 2023

Despite all this, there could be some value in bringing back the dodo in that we are reversing one small sin of of human impact on the planet, and in doing so, we could learn more about a species that was lost to time.

"Bringing back the dodo (or an approximation of it) would undo a little bit of the damage that humans have done to biodiversity, which is a genuinely exciting idea," Julian Koplin, a lecturer in bioethics at the Monash Bioethics Centre in Australia, told Newsweek.

"But developing these techniques is difficult and expensive, and some people are rightly worried that it's not the best use of resources. I understand these worries about opportunity costs, but I personally think it would be useful to have the kinds of techniques that Colossal are developing in our toolkit. And the costs could well come down over time, at which point these worries would be much less serious."

It also may be a way to get the general public excited about conservation, with such a charismatic and legendary creature making a reappearance.

"Maybe bringing back the dodo (or something like it) would be a powerful and inspiring success story that can get people excited about ecological issues in a way that gloomy reports about extinctions just can't," Koplin said.

Alternatively, it could have the complete opposite effect, indicating to people that perhaps there is no point in protecting wildlife if we can simply bring them back to life if we make them go extinct.

"Or maybe these efforts will make people unreasonably sanguine about the extinction of other species," Koplin said. "Will we still care about protecting existing species and ecosystems if technology could theoretically bring them back at a later date?"

"I'm not sure which of these possibilities is more likely to happen—but I think it's important to keep an eye on, because these kinds of shifts in how we think about the environment could be profound."

Do you have an animal or nature story to share with Newsweek? Do you have a question about de-extinction? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.